Food Forest Plates

Diversity -- in our communities and on our plates.

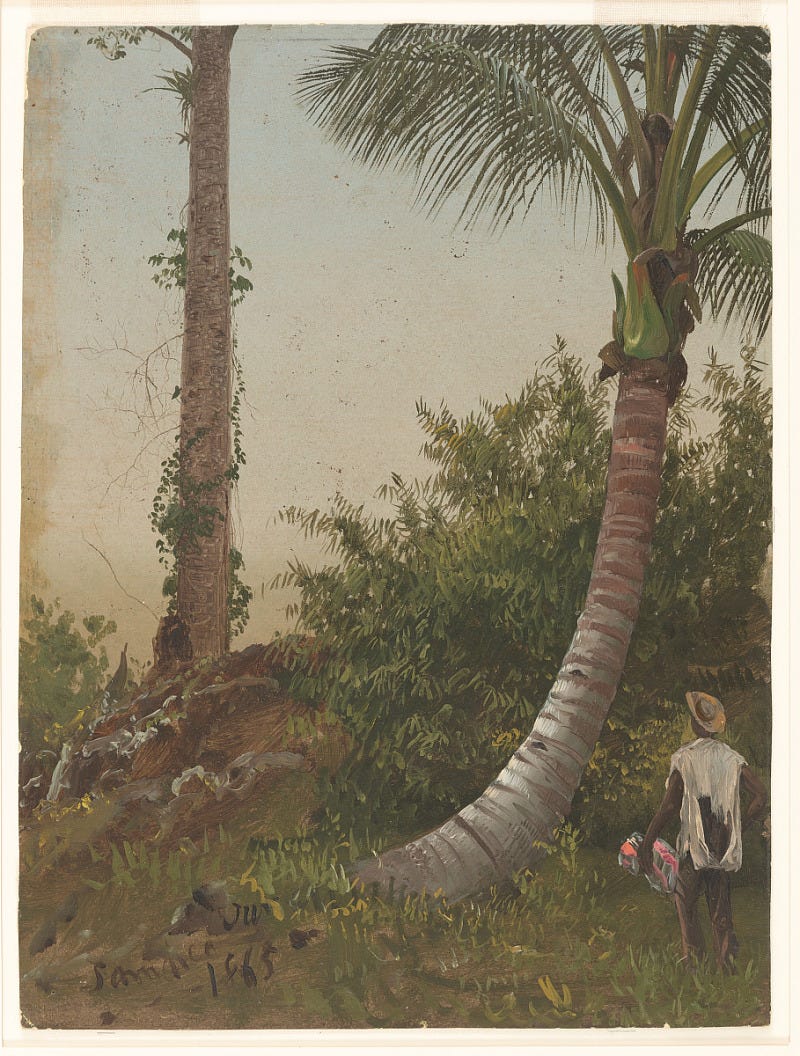

During a graduate school trip to Peru, I visited an agroforest. My sensory memories of the visit are vague – lots of green, lots of fruit trees, damp – but the feeling is still specific and immediate, more than 10 years later. It was like being in heaven – a pure feeling of peace and contentment. My friend Jason teases me about my predilection for functional art. It was a piece of divine functional art, displayed on this godforsaken planet.

After grad school, I secured a dream research assignment: studying the feasibility of Rainforest Alliance (RA) certification for smallholder rubber farmers in the Western Ghats in India (though I lived in Bangalore). The organization I worked with is called FERAL - they do amazing work.

The Western Ghats is a lush mountain range and biodiversity hotspot, teeming with life and beauty. But you know the drill: much of the diverse nature there has been razed to build monoculture plantations, each square meter of land maximized to deliver value by focusing on one crop and one crop only — in this case, often tea and rubber for export outside of India. RA was there to help landowners adopt environmentally friendly practices. If they did, they would earn RA certification and be able to charge their customers a premium. Many of the standards revolved around taking the “mono” out of “monoculture,” to increase the variety of crops they grow on their fields.

Consider the structure of this certification model. First, a bunch of men from the West come to India and wreak insane havoc. Then, a half-century later or so, a much smaller group from the West, now consisting of both men and women, come in to solve the problems created by the first group. The power difference and the awareness of the power difference is the same. The brazen pride has simmered down to a quiet condescension.

During a work trip to Kerala, I sat in on a meeting with RA, a group of Indian bigwig rubber farmers and NGO reps. It’s the only work meeting I’ll remember for the rest of my life. The RA rep was a European woman (I forgot the exact country). Tensions were …. well, not high, actually. Everyone was pretty jovial. If you’re on the top of the food chain, whether in agriculture or civil society, in any country, life is pretty good.

These people gathered to negotiate the set of standards that landowners must adopt to achieve RA certification. One proposed standard highlighted the elephant in the room — or pointed to it and laughed. The RA rep proposed something along the lines of, each laborer must have a bed to sleep on sized xx dimensions. The landowners burst out laughing — in that part of India, they themselves slept on cots. Cots were not perceived as a sign of poverty. The RA rep said in her euroaccent, “ah, alright, this one is — how do you say — over the top?”

Years later, when I started Climate Cookery as a food business, my goal was to make my own contributions to the problems of our food and ag systems, in a way that’s more organic and less cringe-y.

The truth is, certification systems such as Rainforest Alliance or Fair Trade are easy to criticize, but they’ve done a lot of good, too. They’ve successfully introduced the problems of and solutions to concentrated agriculture to many new groups of people, including influential policymakers and business people.

But there are two solutions that address the root of the monoculture problem that we can execute at home, without helicoptering into other countries and being so awkward.

The first is policy: robust government policies that give large, highly concentrated and rich ag operations no choice but to integrate environmental destruction into their business plans. And I think we need to Lina Khan the hell out of Big Ag to make this happen!

I credit the Biden administration for taking meaningful steps to advance agroforestry/agricultural diversification in the US. Biden delivered unprecedented funding under the USDA’s climate-smart commodities program to farmers to adopt measures to increase the variety of things they grow — simple steps such as alley cropping, or planting trees or shrubs between crops to boost biodiversity. Trump is of course destroying these efforts to treat the land with kindness, to generate and care for more life, to add more beauty to the world.

The second and foundational solution is genuine consumer for crops beyond soy, corn and wheat (and by proxy to all — meat), so that farmers have financial incentives to grow a diverse range of crops. Genuine consumer demand for regenerative foods like beans and buckwheat that comes not from guilt, not as a way to assert moral superiority, not even to avoid robust government fines. But rather, from a desire to discover new things, to enjoy the flavor, to feel good about eating nutritious food.

“Food forest” is one of my favorite phrases. It’s a lovely framing to change the way we eat and produce food. There are lots of great I solutions out there to address the problems of industrial agriculture’s role in environmental and human health destruction. Creating food forests — on cornfields and plantations, on street lots and backyards, and on our plates — lies at the base of all these solutions.

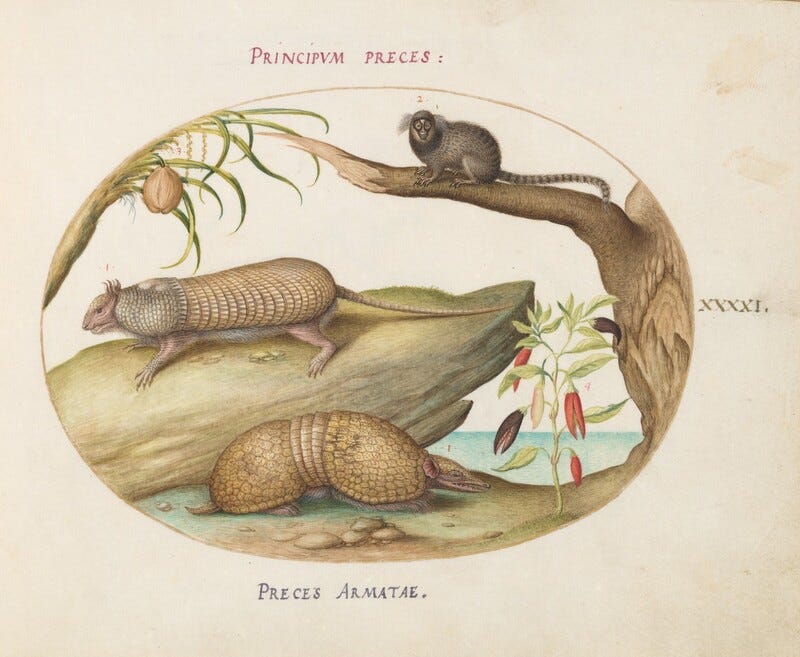

In this newsletter, I plan to expand on the concept of food forests by making and documenting a series of food forest plates focused on foods that I love, but that are also at the center of deep problems in our food systems:

Corn

Milk

Vanilla

By food forest plates, I mean creating a single meal that includes crops that are grown synergistically with the above crops in a real-world food forest system. They exist, and we need many more of them. I’ll explore how we can individually rethink these foods and our relationships to them in a way that minimizes harm. Is it possible?

Li’l Nubs

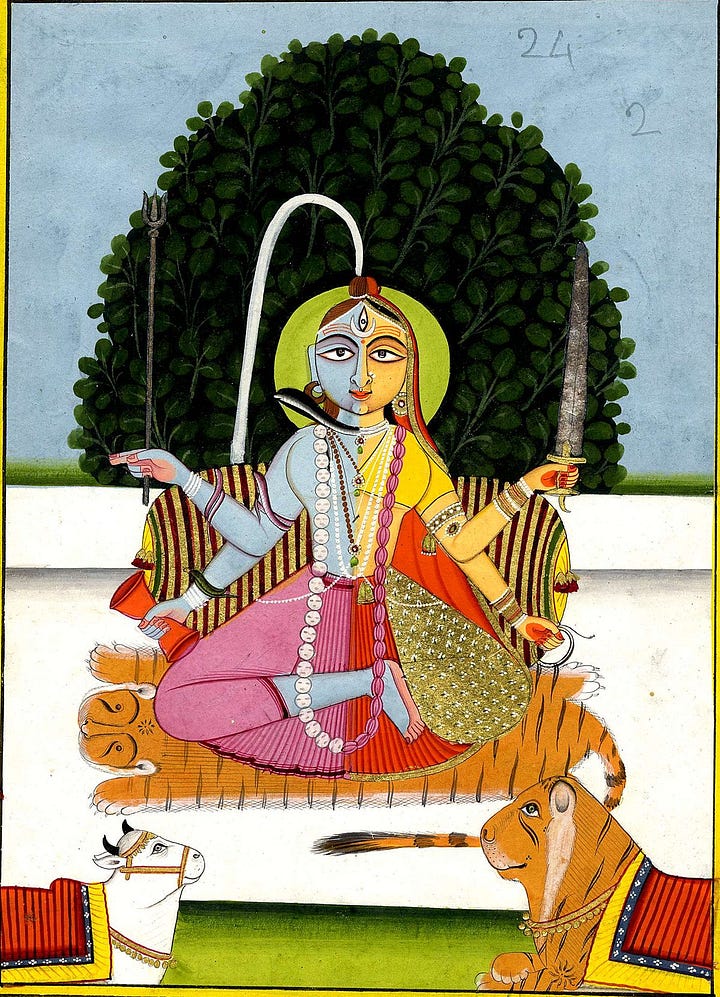

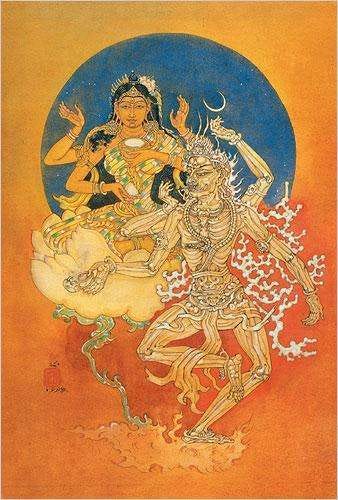

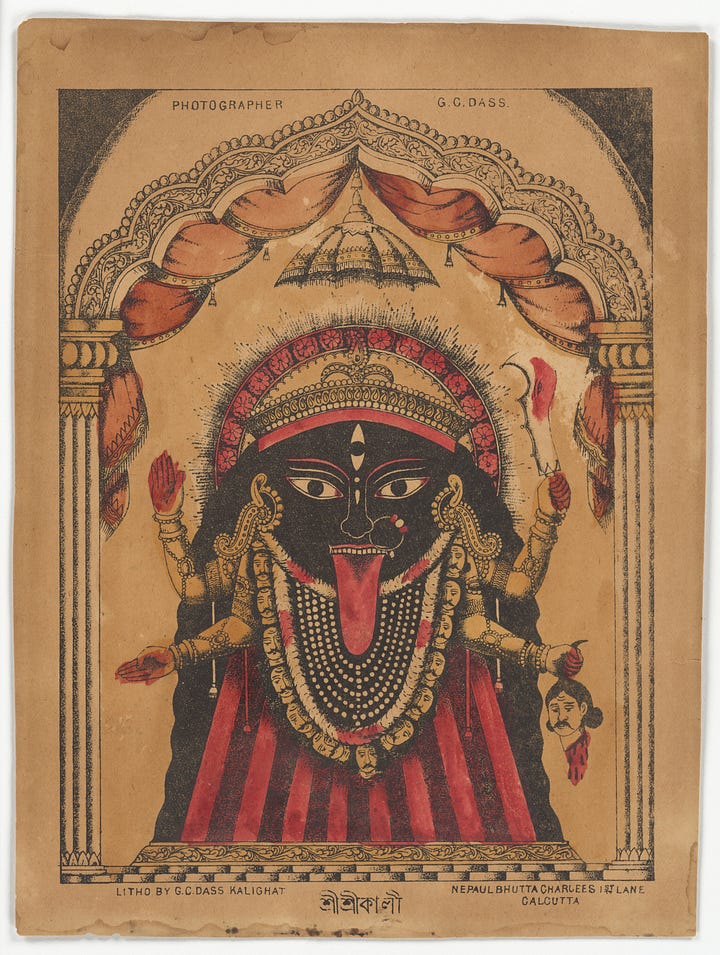

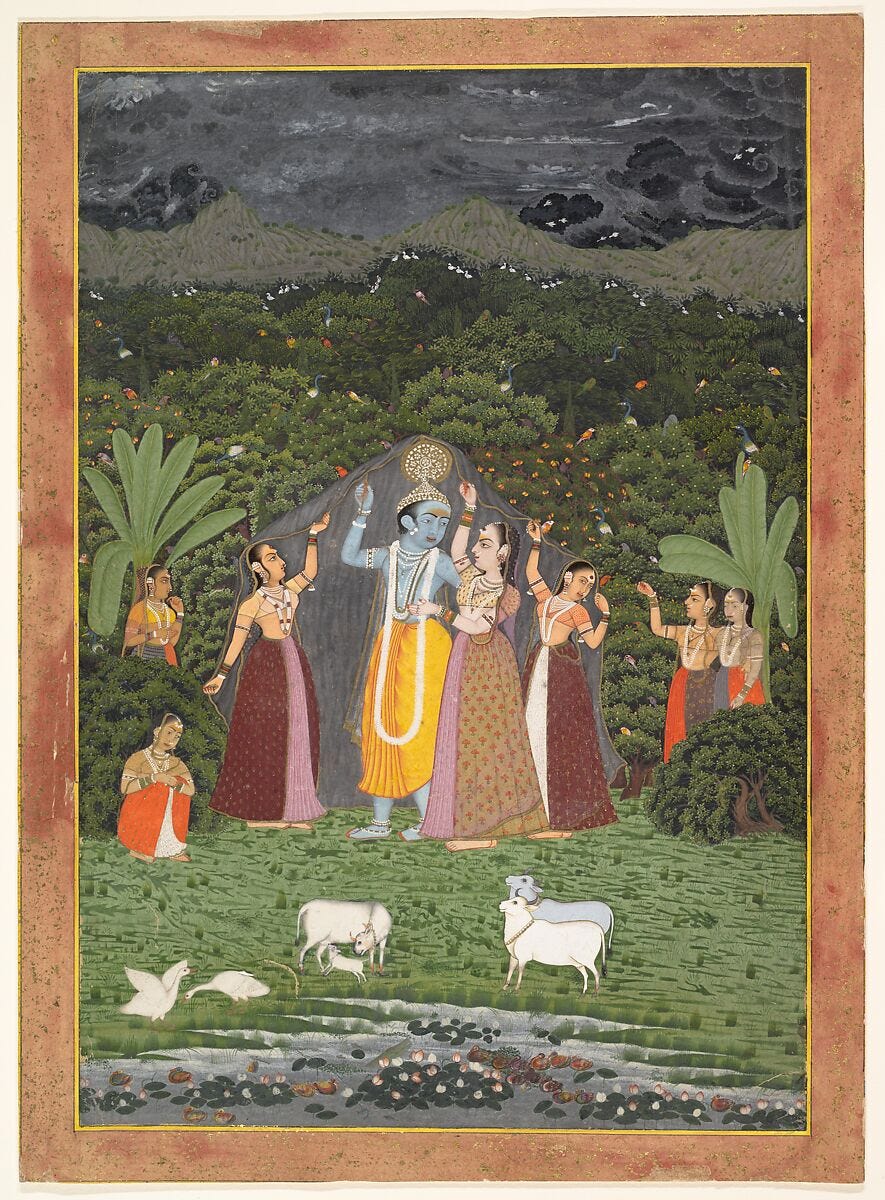

I will also continue my 10 Hindu Goddesses, 10 Recipes series! What can I say, I love a newsletter series. Here are the four I’ve written so far: